Mark is the owner of a beautiful Cessna 185 Skywagon based in the San Francisco Bay area, but the episode I’m about to describe could just as easily have happened to a Cirrus owner. A while back, Mark and his wife traveled to Minden, Nevada, in his airplane to visit with his mother-in-law who was ill. A few days later, they returned to the airport intending to fly home. When Mark started the Skywagon’s engine – a Continental IO-520 – he saw just about the last thing a pilot wants to see: The oil pressure gauge never budged from the zero mark.

After a brief period of “This can’t be happening!” Mark shut down the engine and started thinking about what to do next. It was a Sunday, of course. (These things always seem to happen on weekends when all the maintenance shops on the field are closed.) The only sign of life at this non-towered airport was the presence of a couple of linemen at the airport’s sole FBO.

Mark approached one of the linemen and asked if he knew of any A&P mechanics in the area that might be able to help with his predicament. The lineman rummaged around in the office and emerged with the phone number of a local A&P who lived nearby. Mark called the number, explained his exigency and the mechanic suggested he have the FBO tow the aircraft to his maintenance hangar and promised to meet him there. Little did he anticipate the drama that would unfold over the next few hours.

The A&P’s Diagnosis

When the two met up at the hangar, the mechanic’s first few steps were reasonable and prudent. The first thing he did was to check the dipstick to make sure there was plenty of oil in the sump; there was. Next, he verified the symptom reported by Mark by plumbing a calibrated pressure gauge into the oil system and starting the engine. Both the cockpit gauge and the external gauge read zero, confirming that this was a real lack of oil pressure and not just an indication problem with the cockpit gauge.

The A&P removed the oil filter, cut it open and inspected its contents. He then told Mark that there was “significant bearing metal in the filter” and informed him that the engine would need to be torn down. While Mark was still processing this unexpected bad news, the A&P disappeared into his office for a few minutes and emerged with a written estimate for the engine removal, teardown and reinstallation totaling something well north of $10,000.

Mark was now in a complete state of shock. He was stuck somewhere he didn’t want to be. Some mechanic he'd never met before and didn't know whether to trust was telling him his engine was toast. Mark was way outside of his comfort zone. He felt he needed an expert second opinion before approving such a drastic course of action. He placed a call to my company, hoping someone would answer on a Sunday and wound up speaking with me.

Figure 1: The photo of Mark’s oil filter didn’t exhibit anything exciting

My Second Opinion

Mark briefed me on his situation and sounded like a pretty maintenance-savvy owner. After establishing that both of us had iPhones®, I asked him to send me a couple of photos of the oil filter media that the A&P had described as containing “significant bearing material” so I could assess the magnitude of the disaster. A few minutes later, I received several photos of the filter media including Figure 1 (above).

I examined the photos under magnification and saw only a small amount of what appeared to be aluminum. It didn’t strike me as being a significant quantity, and it certainly didn’t appear to be bearing material. In my judgment, this sure didn’t seem like anything that justified the drastic step of tearing the engine down.

I phoned Mark and explained to him that by far the most likely cause for lack of oil pressure at engine start was some sort of foreign matter contaminating the oil pressure relief valve (PRV). The PRV is what regulates engine oil pressure. It’s a simple device consisting of a spring-loaded plunger that is designed to open when oil pressure reaches a certain level, typically about 50 PSI for Continental engines and 70 PSI for Lycoming engines, to bypass excess pressure from the pump and limit it to the desired value. If foreign matter gets into the PRV during engine operation and prevents it from closing properly, then at the next startup oil pressure will bypass the pump resulting in a low or even zero pressure indication on the gauge.

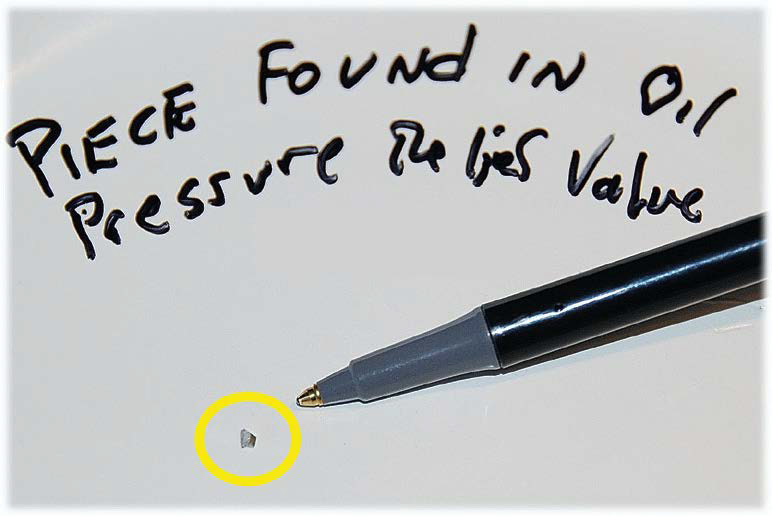

Figure 2: This tiny chunk of aluminum lodged in the PRV accounted for the lack of oil pressure at startup.

I suggested that Mark ask the A&P to unscrew the PRV housing and inspect it for contamination, and I asked that Mark report back with the A&P’s findings. About 30 minutes later, Mark sent me the photo labeled as Figure 2.

I asked Mark to check the tiny chunk of metal with a magnet. He reported that it was nonmagnetic. Given that fact plus the obvious silvery color, I concluded it was almost certainly aluminum and not bearing material. I told Mark that I was not particularly concerned about this tiny piece of aluminum “unless there are a bunch of its brothers and sisters in the oil sump.”

Hostage situation?

Mark relayed my thoughts to the local A&P, who still insisted that the engine needed to be torn down. Now Mark began to panic. “What can I do?” he asked me. “Can this A&P ground my airplane? Can he hold it hostage until I agree to the $10,000-plus teardown?”

I reassured Mark that there was no need to panic, and that I would help guide him through this kerfuffle. In the course of our conversation, I learned that Mark was handy with tools, did his own oil changes and other preventive maintenance, and even carried a pretty decent traveling toolkit in his airplane. Since the local A&P appeared to be seriously spring-loaded to the got-to-tear-it-down position and seemed unlikely to cooperate with any other resolution, I suggested that Mark instruct the A&P to put his plane back together, obtain a logbook entry for the work performed so far, pay the fellow for his labor, and get the plane out of the A&P’s hangar pronto.

The A&P reluctantly reassembled the PRV, installed a new oil filter, cowled up the engine, and towed the airplane out of his hangar. He handed Mark an invoice for a couple of hours of labor and a gratuitously nasty logbook entry that made it clear Mark was removing his airplane against the mechanic’s advice. I told Mark not to worry about the nasty logbook entry, not to paste it into his logbook and to throw it away after one year as permitted by FAR §91.417.

Taking Matters into His Own Hands

When Mark started the Skywagon’s engine, the oil pressure came up, as I was confident it would. He sent me another photo (Figure 3).

Figure 3: With the foreign material removed from the PRV, oil pressure was now fine.

I asked Mark to service the engine with fresh oil, which he purchased from the FBO, and then perform an extended run-up, watching the oil pressure needle carefully. He reported back that oil pressure was rock-steady. I then asked him to do a full-power, high-speed taxi down the airport’s 7,400-foot runway. Once again, everything checked out perfectly. Finally, I asked him to taxi back to the FBO, verify that they had a replacement oil filter they could sell him (they did), and then cut open the oil filter that the local A&P had installed. The filter was clean as a whistle.

At that point, I told Mark that I was comfortable with him flying the airplane home. He said he was, too. But since it was now late in the day and Mark and his wife were emotionally spent, he decided to fly the short hop to Carson City where they would remain overnight, and then fly home Monday morning.

The Rest of the Story

Early the next morning, Mark and his wife departed Carson City in the Skywagon, crossed the Sierras overflying Interstate 80, and continued home to the Bay area. The engine performed flawlessly, and the oil pressure never wavered. Once home, Mark cut open the oil filter once again and again it was clean, with no signs of metal.

Figure 4: Draining the oil through cheesecloth showed no more metal chunks in the sump.

Figure 5: This Cessna oil filter adapter is the subject of a recurring AD to make sure the jam nut is torqued properly.

Two weeks later, Mark’s airplane went in for its annual inspection and we found the source of that pesky bit of aluminum that had lodged in the PRV and initiated all this drama. The shop discovered that the engine’s oil filter adapter jam nut hadn’t been torqued properly at the previous annual inspection – this is the subject of a recurring AD – allowing the adapter to vibrate and tear up some of the aluminum threads.

Figure 6: Here’s what happens when the jam nut is too loose.

Just imagine how Mark would have felt had he given in to the A&P’s demand for an engine teardown, only to discover this. That would have been a tragedy! Yet that’s precisely what would have happened had Mark not had the presence of mind to seek a second opinion and the courage to take matters into his own hands.

This article was initially published in the January/February 2020 issue of COPA Pilot