There is a fair amount of confusion and skepticism among pilots and flight instructors alike regarding whether Angle of Attack indicators (AoAI) can make a meaningful difference in reducing loss of control accidents. According to the NTSB, loss of control is the largest cause of general aviation accidents. FAA’s General Aviation Joint Steering Committee (GAJSC) believes that a lack of awareness of Angle of Attack has resulted in loss of aircraft control and has contributed to fatal GA accidents. The committee also believe that increasing a pilot’s awareness of basic aerodynamic effects of Angle of Attack, along with installation of AoAI in cockpits will help reduce the likelihood of loss of aircraft control. The committee believes that Loss of Control accidents occur because pilots deviate from a stabilized approach to landing.

Stabilized Approach Definition

According to the Cirrus Flight Operations Manual, a VFR approach is considered stabilized when all the following criteria are achieved by 500' AGL:

- Proper airspeed,

- Correct flight path,

- Correct aircraft configuration for phase of flight,

- Appropriate power setting for aircraft configuration,

- Normal angle and rate of descent,

- Only minor corrections are required to correct deviations.

Data courtesy of Mark Waddell, COPA Safety & Education Foundation

Even though after-market AoAI have been available for over five years, and Cirrus Aircraft has been installing them in FIKI equipped aircraft, AoAI equipped aircraft still comprise a very small sample of the total number of general aviation (GA) fleet to make a discernible difference in overall accident statistics. Of the approximately 200,000 GA aircraft in the US, only about 10% have some form of AoAI installed in them.

As a CSIP, I fly with many FIKI-equipped Cirrus aircraft pilots. In my experience, the majority do not understand how to use the AoAI, and some are not even aware that their aircraft has one. The Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH) has no mention of it. Yet it is an instrument available to the pilot on the PFD.

Many Cirrus pilots continue to experience loss of control on landing, primarily because they carry too much speed on final. During a 15-month period, Cirrus pilots had 40 landing accidents, and one fatal accident while landing. According to the FAA, there is a fatal accident attributed to loss of control every three days. Clearly, there is an opportunity to reduce landing, takeoff, approach, and go-around accidents by incorporating proper use of AoAI.

The Problem with Pilots Operating Handbook (POH) Speeds

Pilots are taught to fly POH speeds that are always calibrated for maximum gross weight. However, they can never legally land at maximum gross weight. The approach speed for weight less than maximum gross is lower than that for maximum gross weight, but the POH does not have that data. Many Cirrus pilots use a rule of thumb of reducing approach speed by one knot for every 100 lbs. of weight under gross. How often can pilots be sure that they are doing the mental calculation correctly?

What Angle of Attack Is, and Isn’t

Angle of Attack is the angle at which the chord of an aircraft’s wing meets the relative wind, i.e. the path of the aircraft. It is not the angle at which the nose is pointed relative to the horizon (attitude). Nor is it the angle at which the chord of the wing is set relative to the aircraft’s longitudinal axis (angle of incidence).

In straight and level steady state flight, an airplane will fly as long as wings generate lift (equal to weight) and there is enough thrust to pull the airplane through the airmass (equal to drag).

The wing’s Angle of Attack affects the amount of lift generated. At Critical Angle of Attack, lift generation rapidly decreases, and the wing stalls.

Lift vs. Energy

Angle of Attack is a direct measure of lift, and an indirect measure of kinetic energy. Airspeed is a direct measure of kinetic energy. An airplane can have a lot of airspeed, and still stall if the wing exceeds critical Angle of Attack. An airplane can stall at any speed and in any attitude. But it will always stall at the same critical angle of attack, regardless of weight, attitude, or power setting.

A Brief History of AoAI

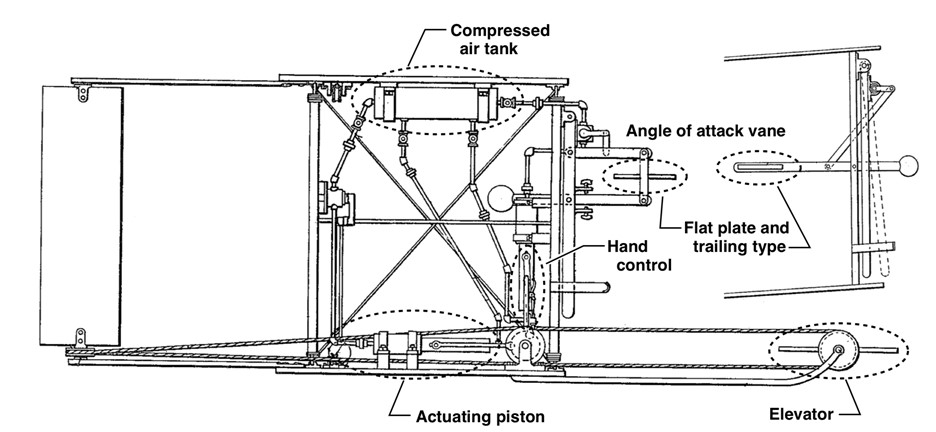

The first AoAI was patented by none other than the Wright Brothers in 1908. It was a marvel of mechanical engineering that gave the pilot crucial information on how much lift they had in each phase of flight.

The Wright Brothers’ Angle of Attack system. Courtesy NASA

In 1944, Leonard Greene patented an AoAI as the first “wing-mounted lift detector,” after having witnessed a friend crash his airplane and die in a scenario where the airplane seemingly fell out of the sky. He founded Safe Flight Instruments in 1946. The instrument was refined over time, and several patents were granted for improved AoAI systems. The US Air Force and US Navy have been using AoAI since 1958.

AoAI Available to Cirrus Pilots

Many aircraft owners have installed aftermarket AoAI, such as Alpha Systems, Aspen or Garmin. After they have been properly trained in its usage, they start reducing their speed on final (Vref) to be closer to 1.3 times the stalling speed with flaps (Vso) for their actual weight on final. This contributes to enhanced safety. Here is a brief survey of AoAI options available to Cirrus pilots.

Perspective and Perspective Plus Aircraft with FIKI

The Perspective and Perspective Plus software takes the lift information from the Safe Flight lift transducer integrated within the stall warning system on the right wing’s leading edge, and displays it next to the speed tape on the PFD. The display can be configured to either be always on, or to display only when the aircraft is in an approach to landing configuration.

Safe Flight Lift Transducer. Courtesy Safe Flight

The Perspective and Perspective Plus software takes the lift information from the lift transducer, and displays it next to the speed tape on the PFD. The display can be configured to either be always on, or to display only when the aircraft is in approach to landing configuration.

Aspen Avionics Evolution

Aspen Avionics displays are becoming increasingly popular as a replacement for the six-pack gauges among early Cirrus owners. It can display AoA via software calculation without the need for extra probes.

Aspen Avionics Evolution with AoAI built-in. Courtesy: Aspen Avionics

Alpha Systems

Alpha Systems builds another popular AoAI that uses a wing-mounted probe, and a variety of display options including a Head Up Display. The probe can be heated, and the AoAI calibrated to include flap settings.

Alpha Systems AoAI with Head Up Display. Courtesy: Alpha Systems and Laurence Balter

AoAI as a Lift Reserve Gauge

It helps to think of AoAI as a lift reserve gauge. For GA aircraft, they are calibrated to easily display the lift corresponding to approach speed, i.e. 1.3 times Vso.

In an Alpha Systems AoA, it is shows as the blue donut.

In a Perspective or Perspective Plus system, it is shown as a horizontal needle pointing to 3’O Clock position toward an AoA value of 0.6. In this scale, 0.2 is maximum AoA, and 1.0 is stalling AoA. It also shows a green circle for Vref on the airspeed tape.

In an Aspen system, the AoA is displayed as blue for maximum, green for optimal, yellow for caution, and black and yellow diagonal stripe for stalling AoA.

Location of AoAI

Ideally, the AoAI should be mounted in the pilot’s line of sight, as in US Navy’s airplanes. However, it is not always possible to do so, especially for Cirrus Aircraft with FIKI’s built-in AoAI in the PFD, or for Aspen’s Evolution displays. Having the AoAI in the PFD is also a practical solution, followed by commercial jets and turboprops. The AoAI does not fluctuate as much as airspeed, and it is easy to keep it in one’s scan during final approach, without having to fixate on it. It does require some practice to become proficient at including AoAI In the instrument scan.

The Icon A5 has the AoAI mounted at the top of the instrument cluster. In this innovative layout, the AoAI becomes the primary instrument in the scan during maneuvers.

Courtesy: Icon Aircraft

How to Integrate AoAI in Your Flying

AoAI intended for GA use are calibrated to make the AoA corresponding to an approach speed of 1.3Vso easily visible to the pilot, as either a blue donut, or a horizontal needle, or a marker on a color-coded bar. Using this as a guide, a pilot can always fly a stabilized approach at an airspeed that corresponds to the specific weight of the airplane on final.

Pilots should fly with their instructors and verify that their AoAI is indeed calibrated to reflect 1.3Vso. It can be done by observing a full stalling speed in a landing configuration, and then adding 30% to it. Once it is done, all they must do on final is to adjust their airspeed to reflect the optimal 1.3Vso indication on the AoAI.

An added benefit of AoAI is that many systems can warn the pilot if they are getting too slow and getting close to a stall during any phase of flight. By always following a Vref of 1.3Vso, a pilot can be assured of the optimal airspeed for final for any aircraft weight. From there, all one must do is slowly reduce power. And gently touch down every time.

References

FAA Angle of Attack Awareness (https://medium.com/faa/angle-of-attack-awareness-cb6dd739c10c)

FAA Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, Chapter 5 (https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/phak/media/07_phak_ch5.pdf)

Copyright © 2022 Shyam Jha

About the Author

Shyam Jha is a CSIP, CFI, and CFII. He has been flying for over 30 years, and owns a Cirrus SR22 Turbo. He is also a member of the COPA Board of Directors. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect those of any organizations mentioned in the article.